Primer on Jinja Templating – Real Python¶

TODO:

Build a sphinx extension to handle jinja code inside rst|md

Create an sphinx_extension Directive for read jinja template code

You can also find the full source code of the web project by clicking on the link below:

Source Code: Click here to download the source code that you’ll use to explore Jinja’s capabilities.

This tutorial is for you if you want to learn more about the Jinja template language or if you’re getting started with Flask.

Get Started With Jinja

Jinja is not only a city in the Eastern Region of Uganda and a Japanese temple, but also a template engine. You commonly use template engines for web templates that receive dynamic content from the back end and render it as a static page in the front end.

But you can use Jinja without a web framework running in the background. That’s exactly what you’ll do in this section. Specifically, you’ll install Jinja and build your first templates.

Install Jinja

Before exploring any new package, it’s a good idea to create and activate a virtual environment. That way, you’re installing any project dependencies in your project’s virtual environment instead of system-wide.

Select your operating system below and use your platform-specific command to set up a virtual environment:

PS> python -m venv venv

PS> .\venv\Scripts\activate

(venv) PS>

$ python3 -m venv venv

$ source venv/bin/activate

(venv) $

With the above commands, you create and activate a

virtual environment named venv by using Python’s

built-in venv module. The parentheses (())

surrounding venv in front of the prompt indicate

that you’ve successfully activated the virtual

environment.

After you’ve created and activated your virtual environment, it’s time to install Jinja with pip:

(venv) $ python -m pip install Jinja2

Don’t forget the 2 at the end of the package name.

Otherwise, you’ll install an old

version that

isn’t compatible with Python 3.

It’s worth noting that although the current major

version is actually greater than 2, the package

that you’ll install is nevertheless called Jinja2.

You can verify that you’ve installed a modern version

of Jinja by running pip list:

(venv) $ python -m pip list

Package Version

---------- -------

Jinja2 3.x

...

To make things even more confusing, after installing

Jinja with an uppercase J, you have to import it

with a lowercase j in Python. Try it out by

opening the interactive Python

interpreter

and running the following commands:

>>>

>>> import Jinja2

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'Jinja2'

>>> import jinja2

>>> # No error

When you try to import Jinja2, with the uppercase

naming that you used to install Jinja, then you raise

a ModuleNotFoundError. To import the Jinja package

to Python, you must type jinja2 with a lowercase

j.

Render Your First Jinja Template

With Jinja imported, you can go on to load and render your first template:

>>>

>>> import jinja2

>>> environment = jinja2.Environment()

>>> template = environment.from_string("Hello, {{ name }}!")

>>> template.render(name="World")

'Hello, World!'

The core component of Jinja is the Environment()

class. In this example, you create a Jinja environment

without any arguments. Later you’ll change the

parameters of Environment to customize your

environment. Here, you’re creating a plain environment

where you load the string "Hello, {{ name }}!" as

a template.

What you just did may not seem much more impressive than using a formatted string in plain Python. However, this example shows two important steps that you usually perform when using Jinja:

Load a template: Load a source that contains placeholder variables. By default, they’re wrapped in a pair of curly brackets (

{{ }}).Render the template: Fill the placeholders with content. You can provide a dictionary or keyword arguments as context. In this case, you’ve filled the placeholder so that you get the familiar

Hello, World!as output.

The source template that you’re loading can be a literal string. But things get way more interesting when you work with files and provide a text file as a template.

Use an External File as a Template

If you want to follow along with the examples in this

tutorial, then you can go ahead and create a new

folder to work in. Inside your working directory,

create a folder named templates/.

You’ll store any upcoming templates in the

templates/ folder. Now create a text file named

message.txt:

{# templates/message.txt #}

Hello {{ name }}!

I'm happy to inform you that you did very well on today's {{ test_name }}.

You reached {{ score }} out of {{ max_score }} points.

See you tomorrow!

Anke

Imagine that you’re a teacher who wants to send

results to well-performing students. The

message.txt template contains a blueprint for the

message, which you can copy and paste to send later.

Just like in the Hello, World! example, you find

curly braces ({{ }}) in your template’s text.

Next, create a Python file named

write_messages.py:

# write_messages.py

from jinja2 import Environment, FileSystemLoader

max_score = 100

test_name = "Python Challenge"

students = [

{"name": "Sandrine", "score": 100},

{"name": "Gergeley", "score": 87},

{"name": "Frieda", "score": 92},

]

environment = Environment(loader=FileSystemLoader("templates/"))

template = environment.get_template("message.txt")

for student in students:

filename = f"message_{student['name'].lower()}.txt"

content = template.render(

student,

max_score=max_score,

test_name=test_name

)

with open(filename, mode="w", encoding="utf-8") as message:

message.write(content)

print(f"... wrote {filename}")

When you create a Jinja environment with

FileSystemLoader, you can pass the path that

points to the folder of your templates. Instead of

passing in a string, you now load message.txt as

your template. Once your template is loaded, you can

use it over and over again to fill it with content. In

write_messages.py, you render name and

score for each of your top students into a text

file.

Note that the keys of the students dictionary,

along with max_score and test_name, match the

template variables in message.txt. If you don’t

provide context for the variables in a template, they

don’t throw an error. But they render an empty string,

which is usually not desired.

When you call template.render(), you return the

rendered template as a string. As with any other

string, you can use .write() to write it into a

file. To see write_messages.py in action, run the

script:

(venv) $ python write_messages.py

... wrote message_sandrine.txt

... wrote message_gergeley.txt

... wrote message_frieda.txt

You just created a file for each of your students.

Have a look at message_gergeley.txt, for example:

Hello Gergeley!

I'm happy to inform you that you did very well on today's Python Challenge.

You reached 87 out of 100 points.

See you tomorrow!

Anke

The variables of your message.txt template

successfully received your student’s data. What a

great way of getting Python and Jinja to work for you!

You can now copy and paste the text, send it to your

students, and save yourself some work.

Control the Flow in Jinja

So far, you’ve added placeholder variables to the

template text and rendered values into it. In this

section, you’ll learn how to add if statements and

for loops to a template to conditionally render

content without repeating yourself.

Use if Statements

In the example from the previous section, you

programmatically created customized messages for your

top students. Now it’s time to consider all of your

students. Add two students with lower scores to

students in write_messages.py:

# write_messages.py

# ...

students = [

{"name": "Sandrine", "score": 100},

{"name": "Gergeley", "score": 87},

{"name": "Frieda", "score": 92},

{"name": "Fritz", "score": 40},

{"name": "Sirius", "score": 75},

]

# ...

You add the scores of Fritz and Sirius to the

students list. Unlike the other students, both

performed below eighty points. Use the 80 mark to

create a conditional statement in message.txt:

1{# templates/message.txt #}

2

3Hello {{ name }}!

4

5{% if score > 80 %}

6I'm happy to inform you that you did very well on today's {{ test_name }}.

7{% else %}

8I'm sorry to inform you that you did not do so well on today's {{ test_name }}.

9{% endif %}

10You reached {{ score }} out of {{ max_score }} points.

11

12See you tomorrow!

13Anke

In addition to the variables that you used before,

you’re now also using a conditional statement with a

Jinja block. Instead of using a pair of double

curly braces, you create Jinja blocks with one curly

brace and a percent sign ({% %}) on each end.

While you can think of the normal variables as

substrings, Jinja blocks wrap a larger section of your

template. That’s why you also need to tell Jinja where

your block ends. To close a block, you use the exact

same keywords again, with an end prefix.

In the example above, you’re starting an {% if %}

block in line 5, which you close in line 9 with

{% endif %}. The if statement itself works

like conditional statements in

Python.

In line 5, you’re checking if score is higher than

80. If so, then you’re rendering a happy message.

Otherwise, you render an apologetic message in line 8.

In the example above, the students agreed that they

wanted eighty points as the benchmark for their Python

challenge performance. Feel free to change 80 to

any score that makes you and your students more

comfortable.

Leverage for Loops

You can also control the flow of your templates with

for loops. As an example, you decide to create an

HTML page for your students that displays all results.

Note that all students have consented to show their

results openly in this friendly competition.

Create a new file named results.html in your

templates/ directory:

{# templates/results.html #}

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Results</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>{{ test_name }} Results</h1>

<ul>

{% for student in students %}

<li>

<em>{{ student.name }}:</em> {{ student.score }}/{{ max_score }}

</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

</body>

</html>

Here you’re creating an HTML page that loops through

your students dictionary and displays their

performance. Just like with the {% if %} blocks,

you have to make sure that you close your

{% for %} block with {% endfor %}.

You can combine if statements and for loops to

control the flow of your templates even further:

{# templates/results.html #}

{# ... #}

{% for student in students %}

<li>

{% if student.score > 80 %}🙂{% else %}🙁{% endif %}

<em>{{ student.name }}:</em> {{ student.score }}/{{ max_score }}

</li>

{% endfor %}

{# ... #}

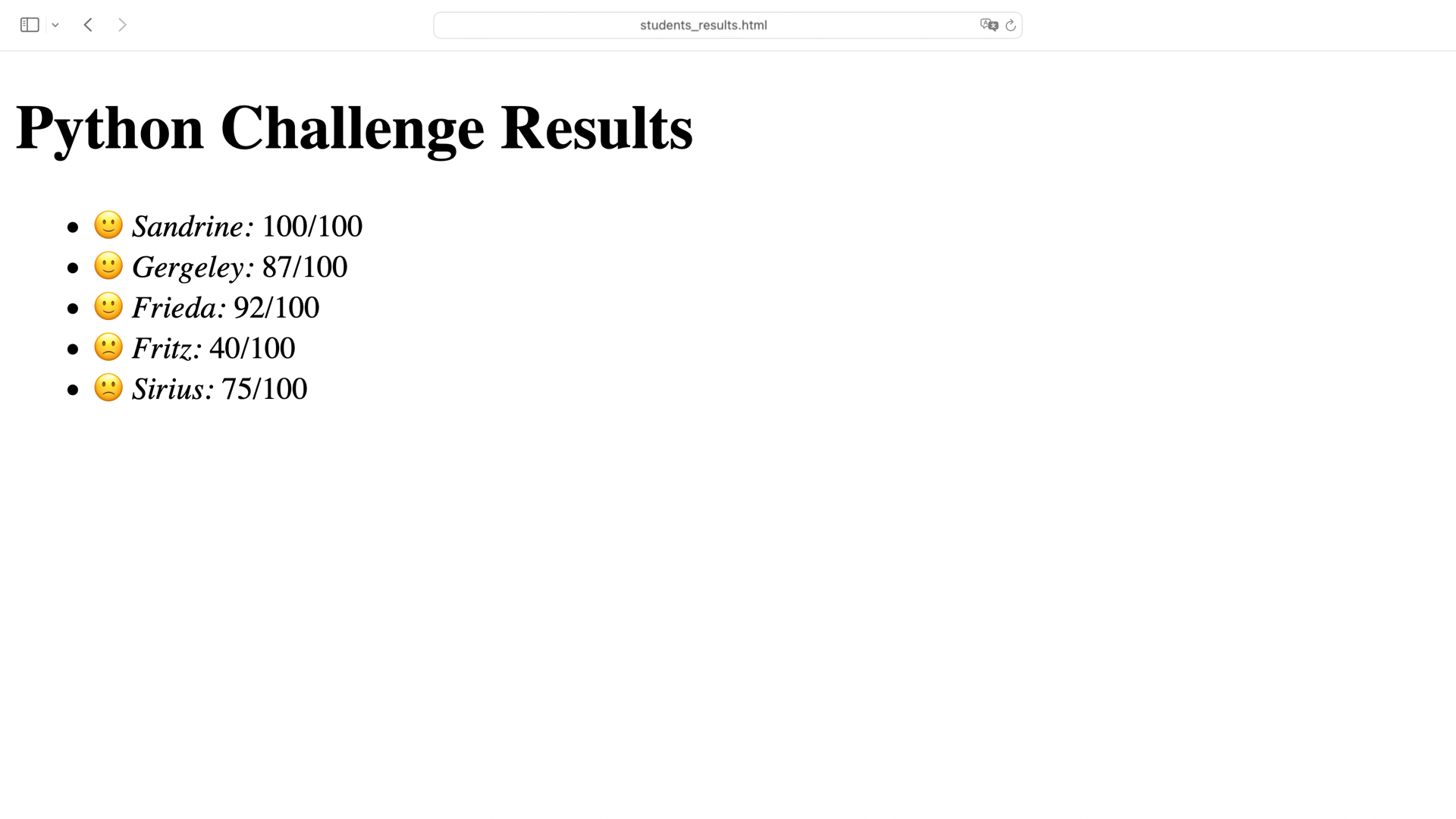

Depending on a student’s score, you show a smiling or a sad face emoji. Note that you can put the block expressions on a single line, too.

Go on and update write_messages.py:

# write_messages.py

# ...

results_filename = "students_results.html"

results_template = environment.get_template("results.html")

context = {

"students": students,

"test_name": test_name,

"max_score": max_score,

}

with open(results_filename, mode="w", encoding="utf-8") as results:

results.write(results_template.render(context))

print(f"... wrote {results_filename}")

In addition to the for loop where you saved a

message for each student, you’re now also writing a

single HTML file containing all the results for that

student. This time you’re creating a context

dictionary that holds all the variables that you pass

into the template.

Note: Using context as a name for the

collection that stores the variables for a template

is a convention. That said, you can name the

dictionary differently if you prefer.

With a dictionary that contains all of your template’s

context, you can call .render() with context

as the only argument. When you run

write_messages.py, you also create an HTML file:

>>>

(venv) $ python write_messages.py

... wrote message_sandrine.txt

... wrote message_gergeley.txt

... wrote message_frieda.txt

... wrote message_fritz.txt

... wrote message_sirius.txt

... wrote students_results.html

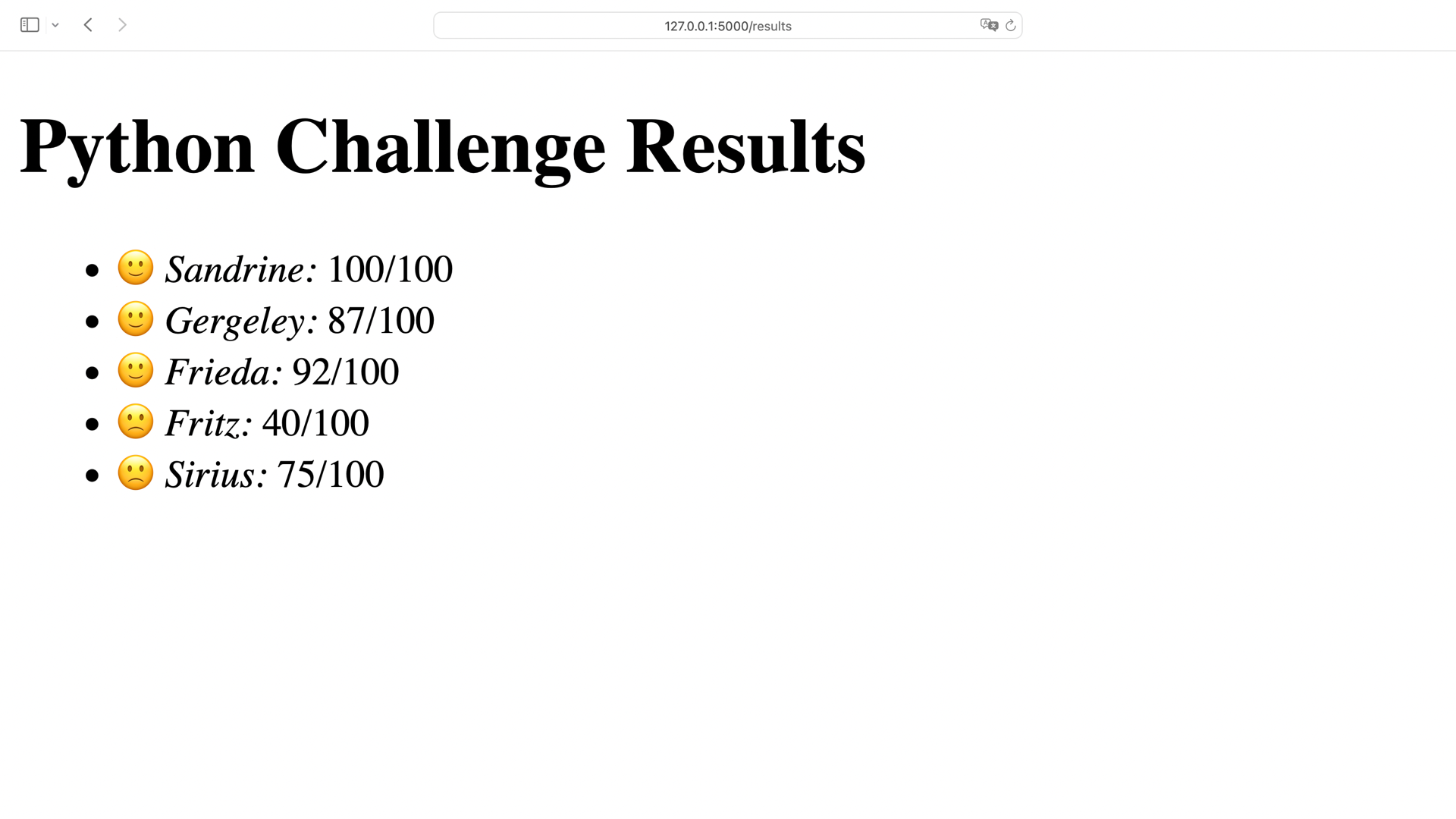

You can view the rendered HTML file in your code editor. However, since you’re working with HTML now, you can also have a look at the file in your browser:

Like in Python scripts, you can control the flow of

Jinja templates with the if statement and for

loops. In Jinja, you’re using blocks to wrap content.

When you’re using a for block, then the content

within that block gets rendered in each step of the

loop.

With templates, you can create building blocks for larger websites without duplicating your front-end code. That’s why web frameworks like Flask leverage the power of Jinja templates. In the next section, you’ll learn how to use Flask to render data from the back end into the web pages of the front end.

Use Jinja With Flask

Chances are that you first heard of Jinja when you used a web framework like Flask. Both Jinja and Flask are maintained by Pallets Project, a community-driven organization that takes care of Python libraries that power the Flask web framework.

In this section, you’ll continue the examples from before by creating a basic web application for your students.

Install Flask

You can continue working in the same directory and virtual environment that you created in the previous section. When you’re in your active virtual environment, go on and install Flask:

(venv) $ python -m pip install flask

With Flask installed, continue to create your first

route to verify that Flask works as expected. Create a

file named app.py in your project’s root

directory:

# app.py

from flask import Flask

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route("/")

def home():

return "Hello, World!"

if __name__ == "__main__":

app.run(debug=True)

When you put an @app.route()

decorator

on top of a Flask view function, you register it

with the given URL

rule.

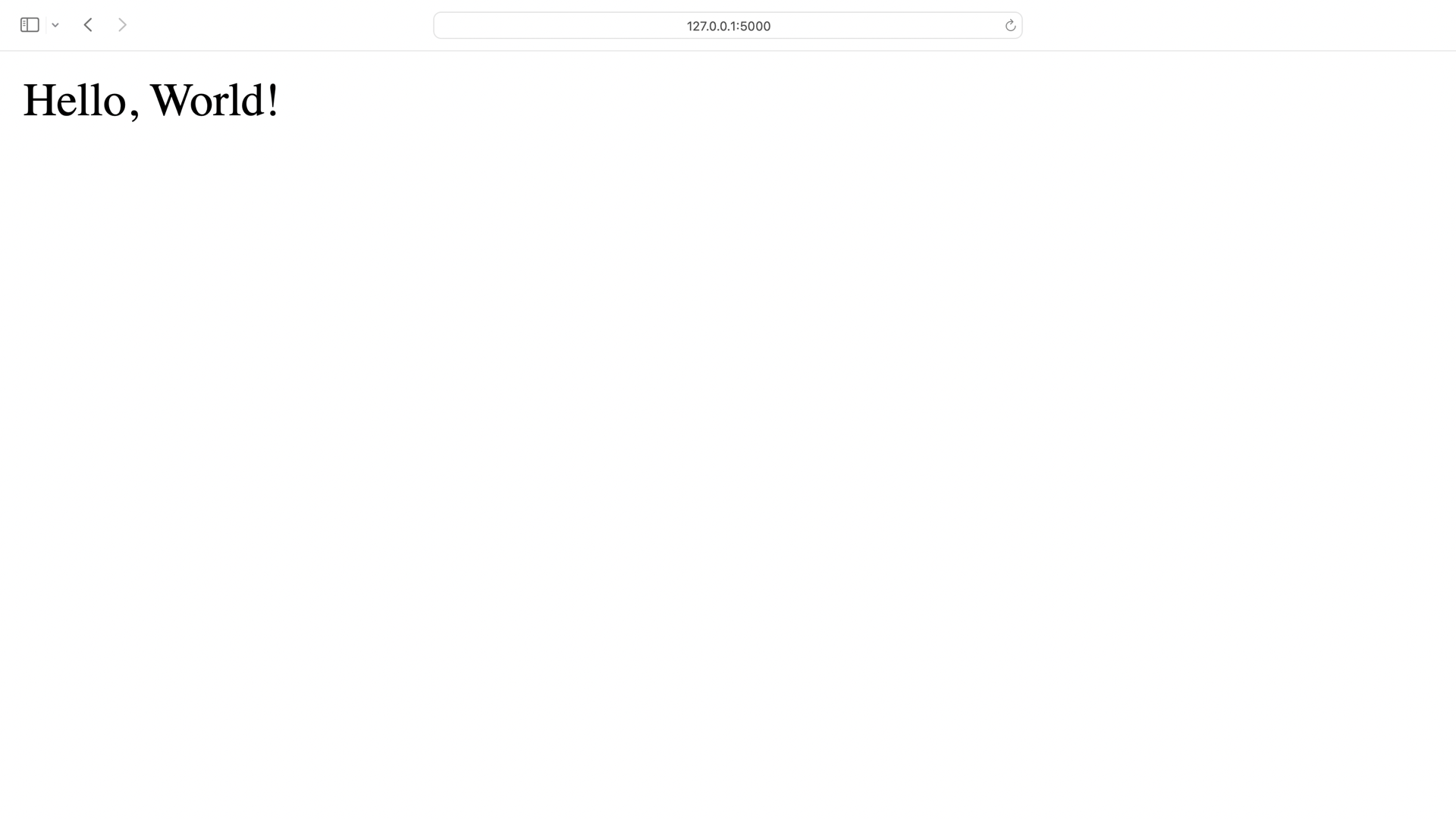

Here, you’re establishing the route /, which

returns Hello, World!.

To see your home page in the browser, start your Flask development web server:

(venv) $ python app.py

...

* Debug mode: on

* Running on http://127.0.0.1:5000 (Press CTRL+C to quit)

* Restarting with watchdog (fsevents)

* Debugger is active!

Now your Flask app is running in debug mode. In

debug mode, you’ll get more meaningful error

messages if something goes wrong. Also, your server

will restart automatically whenever you change

something in your codebase.

To see your home page, visit

http://127.0.0.1:5000:

Awesome, you now have a running Flask app! In the next section, you’ll implement Jinja templates in your Flask app.

Add a Base Template

So far, your Flask app returns a string. You could enhance your string by adding HTML code, and Flask would render it for you. But as you learned in the previous section, using templates makes rendering content much more convenient for you.

Create a new template named base.html in your

templates/ directory:

1{# templates/base.html #}

2

3<!DOCTYPE html>

4<html lang="en">

5<head>

6 <meta charset="utf-8">

7 <title>{{ title }}</title>

8</head>

9

10<body>

11 <h1>Welcome to {{ title }}!</h1>

12</body>

13</html>

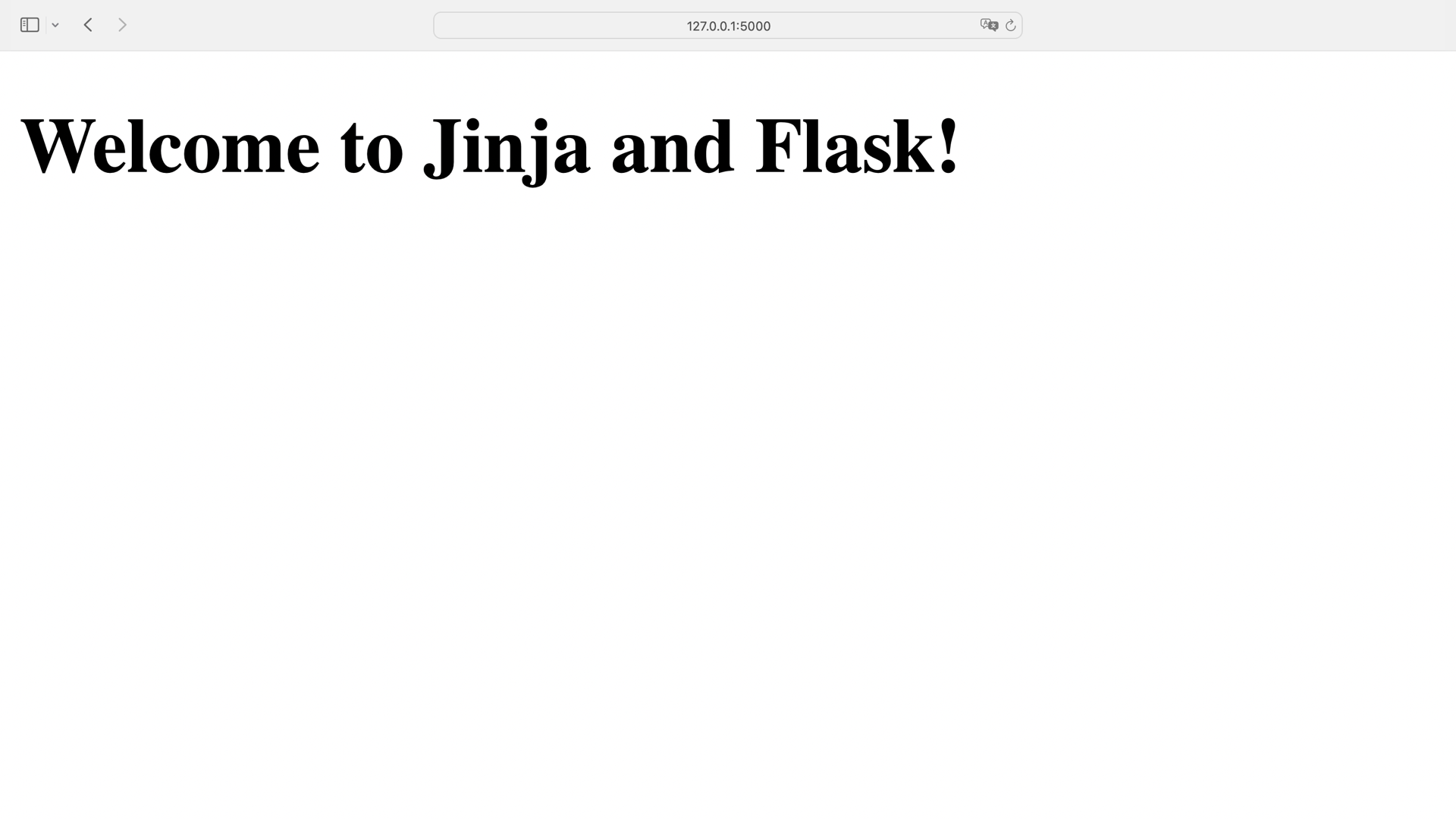

In base.html, you have two occurrences where you

use template variables: once in line 7 and then again

in line 11. To render and serve base.html, load it

as your home page in app.py:

# app.py

from flask import Flask, render_template

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route("/")

def home():

return render_template("base.html", title="Jinja and Flask")

# ...

By default, Flask expects your templates in a

templates/ directory. Therefore, you don’t need to

set the template directory explicitly. When you

provide base.html to render_template(), Flask

knows where to look for your template.

Note: Usually, you’d improve your website’s look with CSS and add some functionality with JavaScript. Because you’re focusing on the content structure in this tutorial, you’ll keep your web app mostly unstyled.

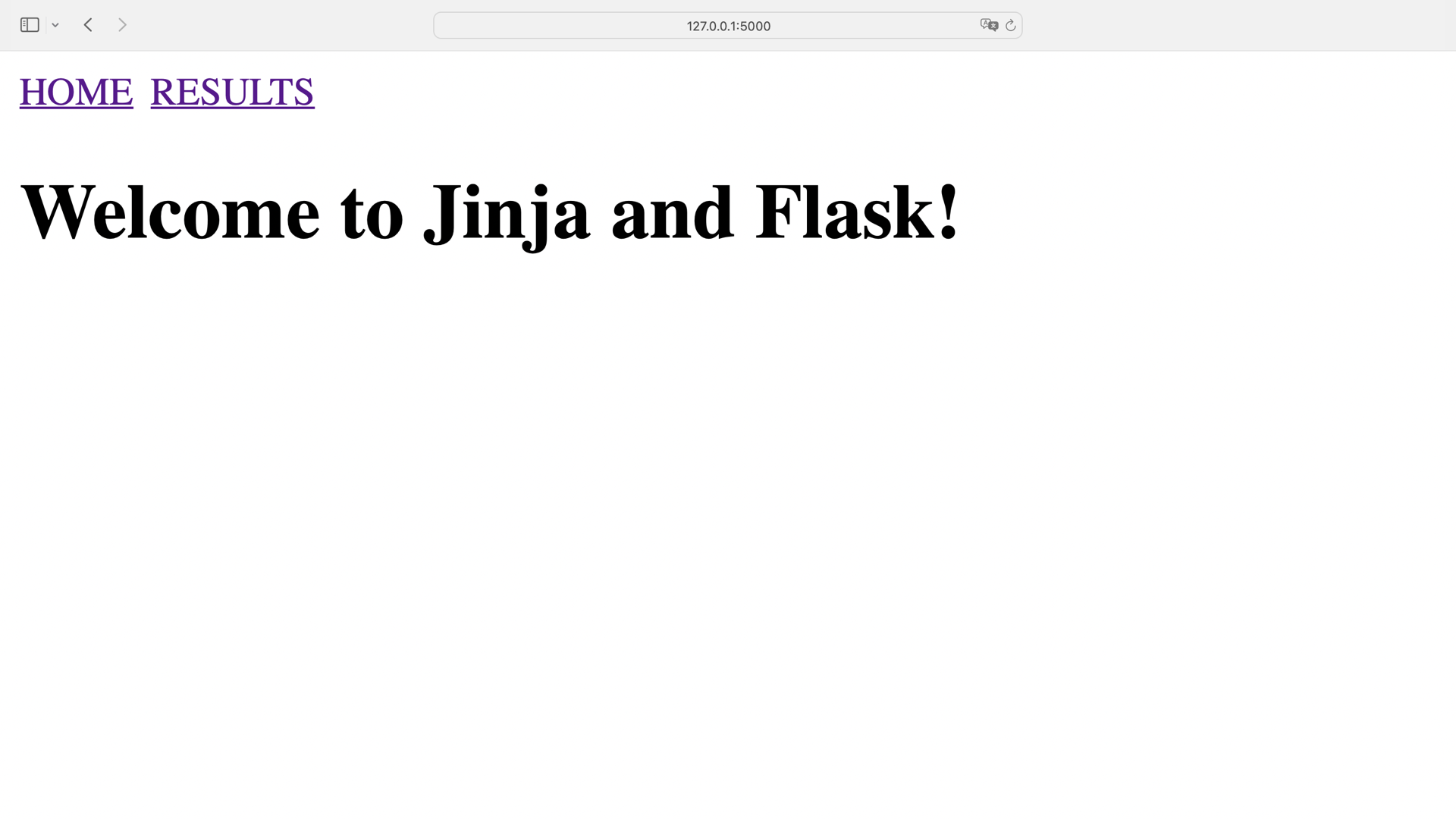

Restart your Flask development server if it hasn’t

updated automatically already. Then visit

http://127.0.0.1:5000 and verify that Flask serves

and renders your base template:

Flask rendered the title variable in your

website’s title and in the welcome message. Next,

you’ll create a page to show your students’ results.

Add Another Page

In one of the earlier

sections, you used

results.html as a template to generate a file

named students_results.html. Now that you’ve got a

web app, you can use results.html to render your

template dynamically without saving it to a new file

this time.

Make sure that results.html is placed in

templates/ and looks like this:

1{# templates/results.html #}

2

3<!DOCTYPE html>

4<html lang="en">

5<head>

6 <meta charset="utf-8">

7 <title>{{ title }}</title>

8</head>

9

10<body>

11 <h1>{{ test_name }} {{ title }}</h1>

12 <ul>

13 {% for student in students %}

14 <li>

15 {% if student.score > 80 %}🙂{% else %}🙁{% endif %}

16 <em>{{ student.name }}:</em> {{ student.score }}/{{ max_score }}

17 </li>

18 {% endfor %}

19 </ul>

20</body>

21</html>

The only adjustments to the earlier version are highlighted above:

Line 7 adds a dynamic page title.

Line 11 enhances the first headline.

To access the results page in your web app, you must

create a route. Add the following code to app.py:

# app.py

# ...

max_score = 100

test_name = "Python Challenge"

students = [

{"name": "Sandrine", "score": 100},

{"name": "Gergeley", "score": 87},

{"name": "Frieda", "score": 92},

{"name": "Fritz", "score": 40},

{"name": "Sirius", "score": 75},

]

@app.route("/results")

def results():

context = {

"title": "Results",

"students": students,

"test_name": test_name,

"max_score": max_score,

}

return render_template("results.html", **context)

# ...

In a full-fledged web app, you’d probably store data

in an external

database.

For now, you keep max_score, test_name, and

students next to results().

Flask’s render_template() accepts only one

positional

argument,

which is the template name. Any other arguments must

be keyword arguments. So you have to unpack your

dictionary

with two asterisks (**) in front of context.

With the asterisk operators, you’re passing the items

of context as keyword arguments into

render_template().

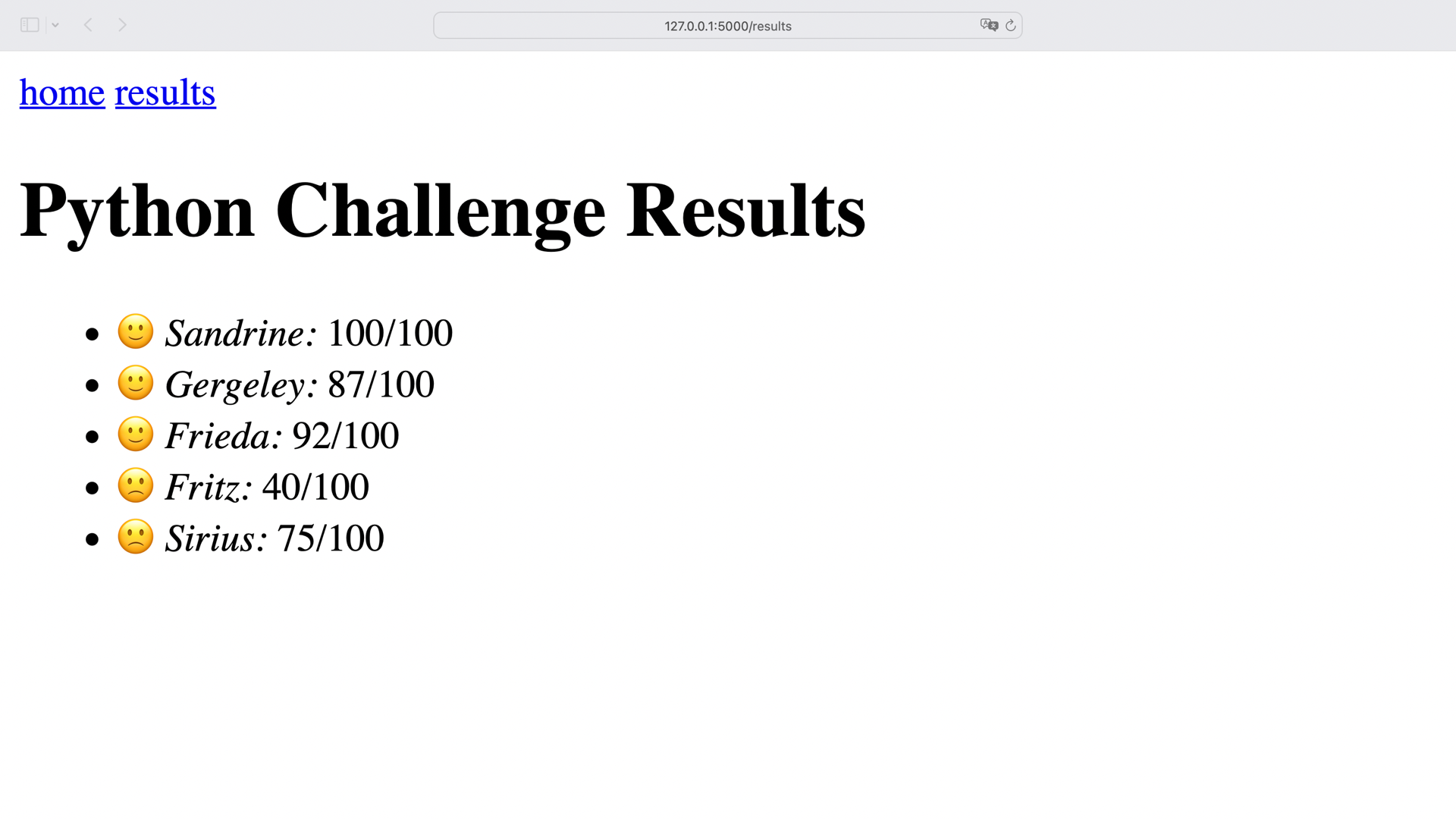

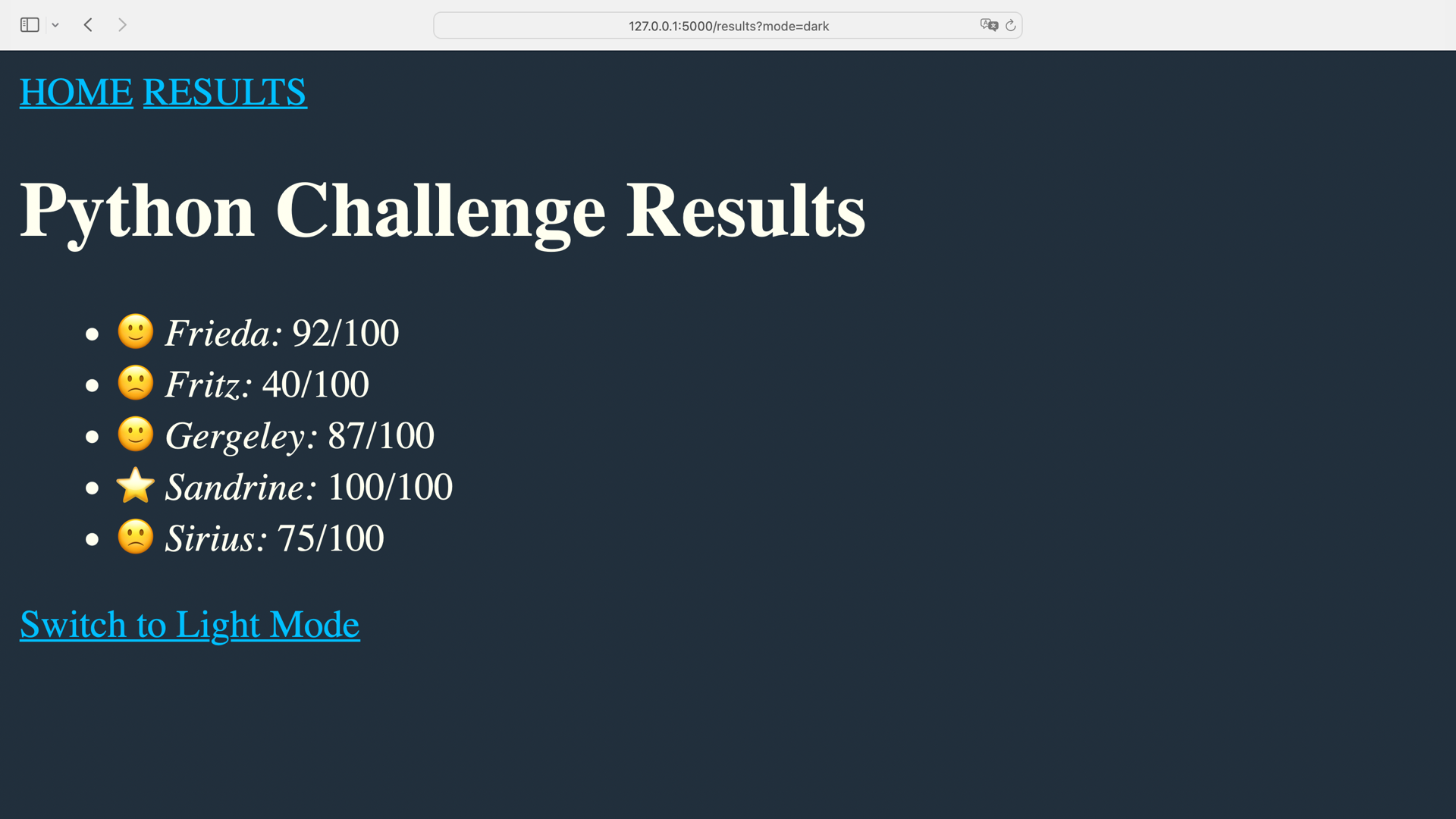

When you visit http://127.0.0.1:5000/results in

your browser, Flask serves results.html with the

rendered context. Hop over to the browser and take a

look at it:

You now have a home page and a page that shows your students’ results. That’s a great start for a web app!

In the next section, you’ll learn how to leverage the power of your templates even more by nesting them. You’ll also add a navigation menu to your project so that users can conveniently jump from page to page.

Nest Your Templates

As your application grows and you continue adding new

templates, you must keep common code in sync. So far,

your two templates, base.html and results.html,

look very similar. When multiple templates contain the

same code, you need to adjust every template if you

change any of the common code.

In this section, you’ll implement a parent and child template structure that’ll make your code much more maintainable.

Adjust Your Base Template

When you use Jinja’s template inheritance, you can move the common structure of your web app to a parent base template and let child templates inherit that code.

Your base.html is almost ready to serve as your

base template. To make your base template extendable,

add some {% block %} tags to the structure:

{# templates/base.html #}

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>{% block title %}{{ title }}{% endblock title %}</title>

</head>

<body>

{% block content %}

<h1>Welcome to {{ title }}!</h1>

{% endblock content %}

</body>

</html>

You use the {% block %} tag to define which parts

of your base template may be overridden by child

templates. Just like with {% if %} and

{% for %}, you must close your blocks with

{% endblock %}.

Note that you also name your blocks. With the

title argument, you allow a child template to

replace the code between {% block title %} and

{% endblock title %} with its own title block.

You can replace the code of {% block content %}

with a content block.

Note: The names of your content blocks must be unique inside each template. Otherwise, Jinja will get confused about which block to choose for replacements.

The content that you have in between the

{% block %} tags in base.html is a

placeholder. The fallback content shows whenever a

child template doesn’t contain the corresponding

{% block %} tags.

You can also decide not to add fallback content in

between {% block %} tags. As with variables in

templates, Jinja won’t complain if you don’t provide

content for them. Instead, Jinja will render an empty

string.

In base.html, you provide fallback content for

your template blocks. Therefore, you don’t need to

change anything in your home() view. It’ll work

the same way as before.

In the next section, you’ll prepare your child

template to work with base.html.

Extend Child Templates

You currently have a results.html template that

works independently, without a parent template. That

means that you can now adjust the code of

results.html to connect it with base.html:

1{# templates/results.html #}

2

3{% extends "base.html" %}

4

5{% block content %}

6<h1>{{ test_name }} {{ title }}</h1>

7<ul>

8{% for student in students %}

9 <li>

10 {% if student.score > 80 %}🙂{% else %}🙁{% endif %}

11 <em>{{ student.name }}:</em> {{ student.score }}/{{ max_score }}

12 </li>

13{% endfor %}

14</ul>

15{% endblock content %}

To connect the child template with its parent

template, you must add an {% extends %} tag at the

top of the file.

Child templates also contain {% block %} tags. By

providing the block’s name as an argument, you’re

connecting the blocks from the child template with the

blocks from the parent template.

Note that results.html doesn’t contain a title

block. But your page will still display the correct

title, because it uses the fallback content in

base.html and the view provides a title

variable.

You don’t need to adjust your results() view. When

you visit http://127.0.0.1:5000/results, you

should notice no changes. The rendered page contains

the root code of base.html and the fill-ins from

the block of results.html.

Keep in mind that any content outside the child

template’s blocks won’t appear on your rendered page.

For example, if you want to add navigation to

results.html that links back to your home page,

then you must either define a new placeholder block in

base.html or add the navigation menu to the

structure of base.html.

The navigation of a website is usually displayed on

every page. With your base and child template

structure, it’s best to add the code for the

navigation menu into base.html.

Instead of adding the navigation menu code directly

into base.html, you can leverage the

{% include %} tag. By referencing another template

with {% include %}, you’re loading the whole

template into that position.

Included templates are partials that contain a

fraction of the full HTML code. To indicate that a

template is meant to be included, you can prefix its

name with an underscore (_).

Follow the prefix-based naming scheme and create a new

template named _navigation.html in your

templates/ folder:

{# templates/_navigation.html #}

<nav>

{% for menu_item in ["home", "results"] %}

<a href="{{ url_for(menu_item) }}">{{ menu_item }}</a>

{% endfor %}

</nav>

Note that _navigation.html contains neither an

{% extends %} tag nor any {% block %} tags.

You can focus solely on how you want to render your

navigation menu.

When you use url_for(), Flask creates the full URL

to the given view for you. So even when you decide to

change the route to one of your pages, the navigation

menu will still work.

Include _navigation.html in base.html to

display your navigation menu on all of your pages:

{# templates/base.html #}

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>{% block title %}{{ title }}{% endblock title %}</title>

</head>

<body>

<header>

{% include "_navigation.html" %}

</header>

{% block content %}

<h1>Welcome to {{ title }}!</h1>

{% endblock content %}

</body>

</html>

Instead of adding the navigation menu code directly

into base.html, you include _navigation.html

into your website’s header. Since results.html

extends base.html, you can visit

http://127.0.0.1:5000/results to check out your

new navigation menu:

Your results page inherits the code from your base template. When you click a link in the navigation menu, the URL in your address bar changes based on your current page.

Apply Filters

Take a moment and think of a situation where another

person takes care of the back end, and your

responsibility is the front end of the website. To avoid

interfering with each other, you’re not allowed to adjust

any views in app.py or change the data that arrives

in your templates.

After a conversation with your students, you agree that your web app could be improved. You come up with two features:

Display the navigation menu items in uppercase.

Sort your students’ names in

results.htmlalphabetically.

You’ll use Jinja’s filter functionality to implement both features without touching the back end.

Jinja provides a bunch of built-in filters. If you check them out, then you’ll notice that they look similar to Python’s built-in functions and string methods.

Before you continue, revisit your _navigation.html

partial:

{# templates/_navigation.html #}

<nav>

{% for menu_item in ["home", "results"] %}

<a href="{{ url_for(menu_item) }}">{{ menu_item }}</a>

{% endfor %}

</nav>

Currently, your menu items are displayed in lowercase

to match the name of the view. If menu_item

weren’t lowercase, then the link wouldn’t work. That

means menu_item in the href attribute must

stay as it is.

However, you can adjust the display of menu_item

inside of the <a> tags:

{# templates/_navigation.html #}

<nav>

{% for menu_item in ["home", "results"] %}

<a href="{{ url_for(menu_item) }}">{{ menu_item|upper }}</a>

{% endfor %}

</nav>

You specify the variable and then a pipe symbol

(|), followed by the filter. In some cases, you

can specify arguments in parentheses.

In your navigation menu, you hand over the

menu_item variable to the upper filter. Like

Python’s .upper() string method, Jinja’s upper

filter returns the variable in uppercase letters.

Visit http://127.0.0.1:5000 to see your changes

live:

Perfect, the menu items are now in uppercase! You implemented the first feature on your request list. Time to tackle the next feature request.

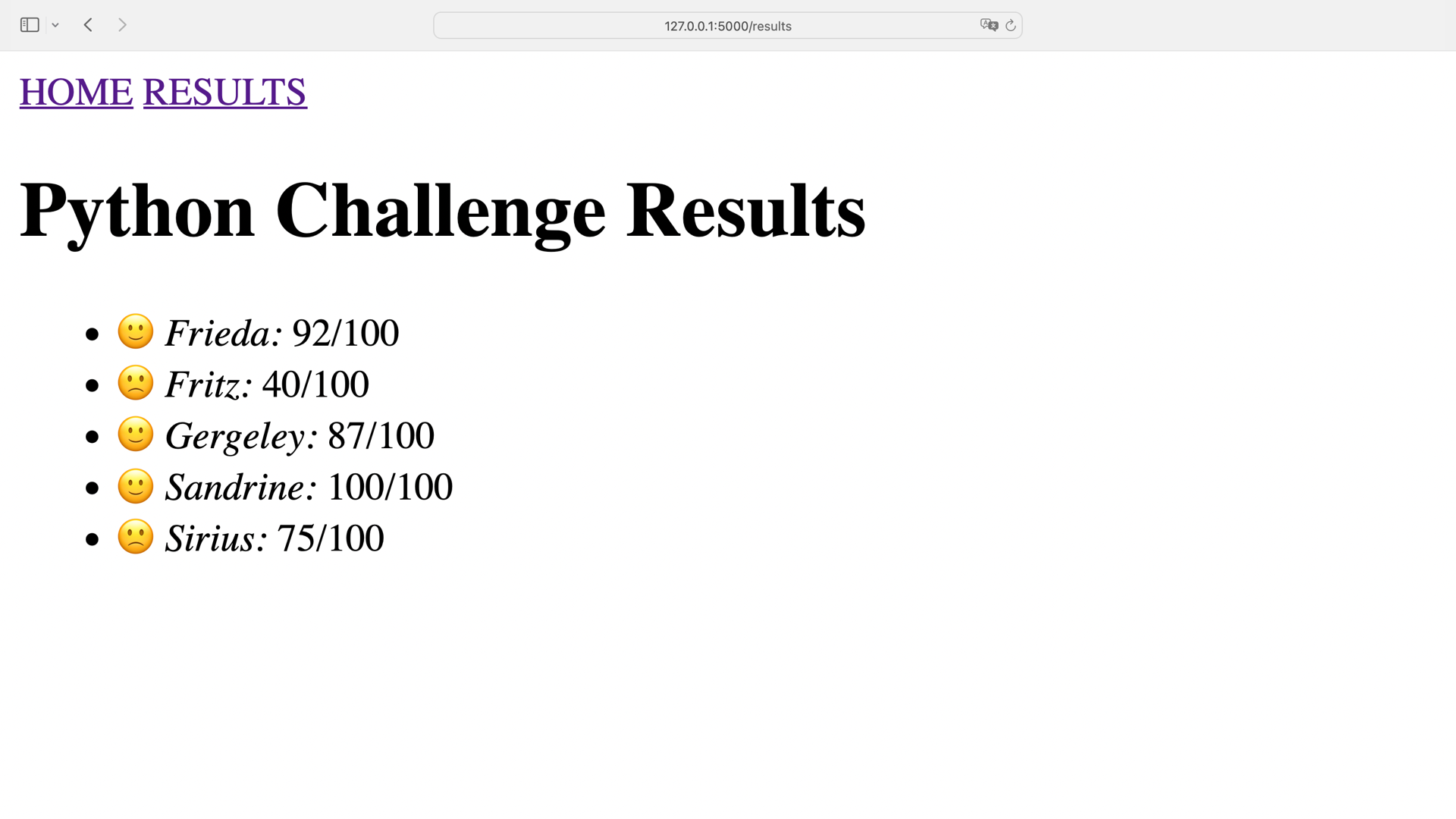

Sort Your Results List

At the moment, your students’ results appear in the

same order as you defined them in the dictionary in

app.py. You’ll use Jinja’s sort filter to sort

the results list alphabetically by student.

Open results.html and add the sort filter to

your for loop:

{# templates/results.html #}

{# ... #}

{% for student in students|sort(attribute="name") %}

<li>

{% if student.score > 80 %}🙂{% else %}🙁{% endif %}

<em>{{ student.name }}:</em> {{ student.score }}/{{ max_score }}

</li>

{% endfor %}

{# ... #}

The sort filter uses Python’s

``sorted()` <https://realpython.com/python-sort/>`__

under the hood.

Your students iterable in results.html

contains a dictionary for each item. By adding

attribute=name, you tell Jinja to sort

students based on the values of name. You can

use the sort filter without any arguments when you

want to sort lists of strings.

Go to http://127.0.0.1:5000/results and check out

the new sorting:

You used Jinja’s sort filter to sort the results

of your students by their names. If you had students

with the same name, then you could chain the filters:

{% for student in students|sort(attribute="name")

|sort(attribute="score", reverse=true) %}

{# ... #}

{% endfor %}

First, you sort your students by name. If there are two students with the same name, then you sort them by their scores. Of course, students with the same name would actually need some differentiation beyond their scores, but for the purposes of the example, this sorting is sufficient.

You reverse the order of score to sort these

students from highest to lowest score. When your lines

get too long, Jinja allows you to distribute your

statements across multiple lines.

Note: In contrast to using Booleans in Python, you should write Booleans in Jinja in lowercase.

You use filters to transform data in your templates independently from your back end. When applying a filter to a variable, you can change the variable’s value for the user without changing any underlying data structure.

Check out Jinja’s filters documentation to learn more about template filters.

If you want to put even more logic into your templates, then you can leverage macros. In the next section, you’ll explore macros by implementing three more features in your Flask app.

Include Macros

When you include partial templates like a navigation menu, the included code is rendered in the context of the parent template without needing any adjustments. Very often, that’s exactly what you want, but other times you may want to customize the appearance of your included templates.

Jinja’s macros can help you create template partials that accept arguments. Like when defining your own functions in Python, you can define macros and import them into your templates.

In this section, you’ll add three more features to your Flask project:

Implement a dark mode.

Highlight the student with the best score.

Mark the current page in the navigation menu.

Like before, you won’t touch any back-end code to improve your web app.

Implement a Dark Mode

For some students, a light-on-dark color scheme is visually more appealing. To cater to all your students, you’ll add the option to switch to a dark mode with light-colored text on a dark background.

Add a macros.html file to the templates/

directory:

1{# templates/macros.html #}

2

3{% macro light_or_dark_mode(element) %}

4 {% if request.args.get('mode') == "dark" %}

5 <a href="{{ request.path }}">Switch to Light Mode</a>

6 <style>

7 {{ element }} {

8 background-color: #212F3C;

9 color: #FFFFF0;

10 }

11 {{ element }} a {

12 color: #00BFFF !important;

13 }

14 </style>

15 {% else %}

16 <a href="{{ request.path }}?mode=dark">Switch to Dark Mode</a>

17 {% endif %}

18{% endmacro %}

You define a macro with a {% macro %} block that

resembles a function definition in Python. Your macro

must have a name, and it can accept arguments.

For the light_or_dark_mode() macro, you must

provide an HTML element name. This will be the element

that the CSS in lines 6 to 14 changes from light to

dark.

To avoid serving a dark-themed website by default, you

want to give your students the option to toggle the

design. When they add ?mode=dark to any route of

your app, you activate the dark mode.

In line 4, you’re using Flask’s `request

object <https://flask.palletsprojects.com/en/2.1.x/reqcontext/>`__

to read the request parameters. The request object

is present in your template’s context by default.

If the dark mode parameter exists in a GET request,

then you show a link with the option to switch to the

light mode in line 5 and add the style tag to the

template. Without any dark mode parameters, you show a

link that toggles to the dark theme.

To use your macros, you must import them to your base

template. Just like with Python’s ``import`

statements <https://realpython.com/python-import/>`__,

it’s recommended to put the {% import %} block at

the top of your template:

{# templates/base.html #}

{% import "macros.html" as macros %}

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>{% block title %}{{ title }}{% endblock title %}</title>

</head>

<body>

{# ... #}

<footer>

{{ macros.light_or_dark_mode("body") }}

</footer>

</body>

</html>

Depending on the GET parameters of a request, you render the dark mode and show a link to switch to the other color theme.

By providing body as the argument for

macros.light_or_dark_mode(), your students can

switch the color scheme of the whole page. Visit

http://127.0.0.1:5000 and play around with your

color scheme toggle:

embed-responsive embed-responsive-16by9 rounded mb-3 border

You can try providing "h1" instead of "body"

to macros.light_or_dark_mode() and then reload the

page. Because macros accept arguments, they give you

the flexibility to conditionally render parts of your

templates.

Highlight Your Best Student

Another reason to introduce macros to your Flask project is to put some logic into its own compartment. Like nesting templates, outsourcing functionality to a macro can tidy up your parent template.

To highlight your best student with a star emoji,

clean up results.html and reference an

add_badge() macro:

{# templates/results.html #}

{# ... #}

{% for student in students|sort(attribute="name") %}

<li>

{{ macros.add_badge(student, students) }}

<em>{{ student.name }}:</em> {{ student.score }}/{{ max_score }}

</li>

{% endfor %}

{# ... #}

Note that you don’t import macros.html at the top

of results.html. You’re extending base.html,

where you’ve already imported all macros. So there’s

no need to import them again here.

Instead of adding more code to a list item in

results.html, you’re referencing

macros.add_badge() inside your for loop. You

take the opportunity to remove the if … else

condition that displayed a happy or a sad face emoji.

This code will perfectly fit the macro’s purpose of

adding a badge to all students.

The add_badge() macro will expect two arguments:

The current

studentdictionaryThe complete

studentslist

If you visited your page now, you’d get an error

because Flask can’t find the macro that you’re

referencing. Go on and add your new macro to

macros.html:

1{# templates/macros.html #}

2

3{# ... #}

4

5{% macro add_badge(student, students) %}

6 {% set high_score = students|map(attribute="score")|max %}

7

8 {% if student.score == high_score %}

9 ⭐️

10 {% elif student.score > 80 %}

11 🙂

12 {% else %}

13 🙁

14 {% endif %}

15{% endmacro %}

Jinja lets you define your own variables inside of a

template with the {% set %} block. When you define

variables, you can also add filters to their values

and even chain them.

In add_badge, your’re defining high_score by

first creating a list of all scores with the map()

filter and then picking the highest score with

max(). Both filters behave similarly to Python’s

``map()` <https://realpython.com/python-map-function/>`__

or `max()

function <https://realpython.com/python-min-and-max/>`__.

Once you know the highest score among your students, then you check the score of your current student against it in lines 8 to 14.

Visit http://127.0.0.1:5000/results and see your

new macro in action:

In addition to the smiling or sad face emoji that you showed before, you now display a star emoji for your best-performing student.

Mark the Current Page

The last feature that you’ll implement will improve your navigation menu. At the moment, the navigation menu stays the same on either page. In this section, you’ll create a macro that marks the menu item of your current page with an arrow.

Add another macro to macros.html:

{# templates/macros.html #}

{# ... #}

{% macro nav_link(menu_item) %}

{% set mode = "?mode=dark" if request.args.get("mode") == "dark" else "" %}

<a href="{{ url_for(menu_item) }}{{ mode }}">{{ menu_item|upper }}</a>

{% if request.endpoint == menu_item %}

←

{% endif %}

{% endmacro %}

Your nav_link() macro takes the menu item as an

argument. If menu_item matches the current

endpoint, then your macro renders an arrow in addition

to the menu item link.

Additionally, you check for the color mode. If

"dark" is part of the GET request, then

"?mode=dark" will be added to the menu link.

Without checking and adding the mode, you’d switch to

the light theme every time you click the link, because

"?mode=dark" wouldn’t be part of the link.

Replace the menu item link in _navigation.html

with your new macro:

{# templates/_navigation.html #}

<nav>

{% for menu_item in ["home", "results"] %}

{{ macros.nav_link(menu_item) }}

{% endfor %}

</nav>

By adding the nav_link() macro to your navigation

menu, you keep your navigation template clean. You

hand down any conditional logic to nav_link().

Visit http://127.0.0.1:5000 and have a look at all

the features that you’ve implemented:

embed-responsive embed-responsive-16by9 rounded mb-3 border

Macros are a powerful feature of Jinja. Still, you shouldn’t overuse them. In some situations, it might be better to put the logic into the back end instead of letting your templates do the work.

There will always be edge cases where you must decide if you add code directly to your template, defer it to an included template, or create a macro instead. If your template code wrestles too much with your data structures, then it might even be a sign that your code logic belongs to the back end of your app.

- name:

author

About Philipp Acsany

© 2012–2023 Real Python ⋅ Newsletter ⋅ Podcast ⋅ YouTube ⋅ Twitter ⋅ Facebook ⋅ Instagram ⋅ Python Tutorials ⋅ Search ⋅ Privacy Policy ⋅ Energy Policy ⋅ Advertise ⋅ Contact